Despite imposing her vast resources to pressure her children to prevent them taking control of the the Hope Margaret Hancock Trust, Gina Rinehart has failed to prevent her daughter Bianca Rinehart from being appointed to replace her as trustee.

Whilst the decision is fairly unsurprising, it is telling in that it reveals the lengths Gina Rinehart went to maintain control of her vast empire. It is also a testament to the strength Bianca Rinehart has shown in persisting with a correct interpretation of the deed governing the trust.

This is a case summary of the decision in Hancock v Rinehart [2015] NSWSC 646 made on 28 May 2015. By Jacob Carswell-Doherty.

The NSW Supreme Court recently handed down a decision which resulted in Gina Rinehart being removed as trustee of the Hope Margaret Hancock Trust (“the Trust”). The trust was set up by the late Langley George Hancock (aka “Lang Hancock”), a well-known Australian mining magnate who died in 1992. The proceedings were initiated by John Langley Hancock and Bianca Hope Rinehart, the son and daughter of Gina Rinehart. The trust is said to hold assets worth in excess of $4billion. This value was largely due to the Trust’s considerable shareholding in Hancock Prospecting Pty Limited.

Summary

- Gina Rinehart and her children were involved in a dispute over Mrs Rinehart’s role as trustee of the Trust.

- The children argued that Gina Rinehart:

– committed a “fraud on a power” by attempting compel them to give up rights they had as beneficiaries of the Trust and this had the effect of conferring personal benefits on Mrs Rinehart; and

– Should be removed as trustee of the Trust. - The Court decided that when contextualised to the nature of the business of Hancock Prospecting Pty Limited and the magnitude and extent of risks which its business experiences and was likely to experience, then the actions taken by Gina Rinehart can be seen as an appropriate attempt to act fairly towards the beneficiaries of the Trust.

- All parties eventually agreed that Gina Rinehart should be replaced as trustee of the Trust. The question was by whom.

- Brereton J decided that Bianca Hope Rinehart should be appointed as trustee of the Trust as she was the “least unsatisfactory” person to perform the role. This was because other proposals were riskier. In particular the appointment of other trustees who were suggested may have resulted in pre-emptive rights of other unrelated third parties being activated, resulting in the Trust potentially losing its considerable shareholding in Hancock Prospecting Pty Limited.

History relating to the proceedings

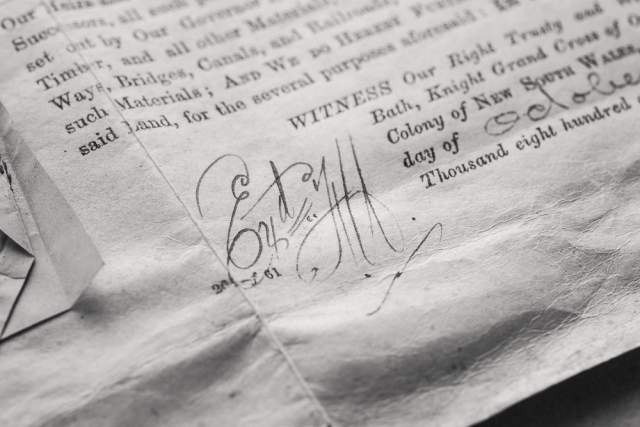

The Trust was created on 27 December 1988 and the terms of the trust deed were later amended on 24 August 1995.

Gina Rinehart was appointed the trustee of the Trust following the death of Lang Hancock in 1992. Mrs Rinehart’ children John Langley Hancock, Bianca Hope Rinehart, Ginia Hope Frances Rinehart and Hope Rinehart Welker were the beneficiaries of the Trust.

According to the terms as at 24 August 1995, the Trust was to vest on 6 September 2011 – the date on which the youngest of Mrs Rinehart’s surviving children attained the age of 25 years.

Three days before the Trust was to vest, Gina Rinehart instructed advisors to send a letter to each of the beneficiaries stating that the Trust’s tax advisors, PricewwaterhouseCoopers, had provided advice suggesting that upon vesting, each beneficiary would become liable to pay capital gains tax on the value of the Trust estate to which they became entitled, which would be “very substantial”.

The letter also represented that the valuable shares that the Trust was holding (and some of which were to be handed over to the children) could never be sold to a “non-Hancock family group member” or otherwise encumbered, due to the existence of another agreement which precluded this from occurring without a lot of things going wrong. The letter concluded that the vesting of the Trust and the consequent CGT liability would therefore lead to the bankruptcy of each beneficiary.

The point of these representations presumably was to create the impression that the vesting of the assets of the Trust would be a CGT event, the beneficiaries would incur a considerable CGT liability and have a hefty tax bill. The beneficiaries could not sell the shares they received to pay for the CGT bill because the shares could only be sold to Hancock family group members.

The solution, according to Gina Rinehart, was to extend the vesting date by the execution of a deed by all of the beneficiaries of the Trust and Gina Rinehart. By executing the deed each beneficiary would be promising not to seek to query or challenge any act or omission of Gina Rinehart in relation to the Trust, and undertaking that if they intended to enter into marriage or a marriage-like relationship they would enter into prenuptial agreement with their spouse to stop that spouse making any claim against the Trust or its assets.

No such deed was ever entered into and in fact it came to light during the early stages of the proceedings that Gina Rinehart had not actually received such advice in relation to the CGT liability on vesting of the trust.

On 4 September 2011, Gina Rinehart went ahead anyway and executed a variation of the Trust Deed so as to extend the vesting date of the Trust to 2068.

On 5 September 2011 proceedings were initiated by John Langley Hancock, Hope Rinehart Welker, Ginia Hope Frances Rinehart and Bianca Hope Rinehart. However, by the end, only John and Bianca were plaintiffs and everyone else became a defendant.

Commencement of the proceedings

The summons commencing the proceedings asked the Court to make the trust vest when the youngest child of Gina Rinehart turned 26 and that Gina Rinehart be removed as trustee of the Trust, with her children to replace her.

Essentially the basis of the proceedings was that by sending the letter and proposing the deed, Gina Rinehart misconducted herself so as to demonstrate that she was unfit to remain as trustee of the Trust.

It was argued that Gina Rinehart misrepresented to her children that they would incur a massive CGT liability as a result of the vesting of shares and would have to declare bankruptcy as a result.

Furthermore, in proposing to only exercise discretion to vary the terms of the Trust to extend the vesting date, in return for a full release from any claim from her children, Gina Rinehart placed undue pressure on her children in order to obtain benefits for herself. The benefits being a release from any claim from the children in relation to the administration of the Trust, as well as enabling her to maintain her grip on Hancock Prospecting Pty Limited.

Fraud on a power

By taking this action, the plaintiffs alleged that Gina Rinehart committed what is known as a “fraud on a power”.

Any power, such as the powers of a trustee of a trust, must be exercised in good faith and for the purpose for which it was given and not for any other ulterior purpose (see Vatcher v Paull [1915] AC 372, 378 (Lord Parker); Cowan v Scargill [1985] Ch 270, 288D (Megarry VC)).

A “fraud on a power” is specifically the exercise of a power for an extraneous purpose. The conduct does not have to be illegal or immoral in the ordinary sense of the word “fraud”. Exercises of power for an extraneous purposes are invalid and void, as Dixon J said in Mills v Mills [1938] HCA 4; (1938) 60 CLR 150 (at 185):

“[Trustees] are fiduciary agents, and a power conferred upon them cannot be exercised in order to obtain some private advantage or for any purpose foreign to the power. It is only one application of the general doctrine expressed by Lord Northington in Aleyn v Belchier: “No point is better established than that, a person having a power, must execute it bona fide for the end designed, otherwise it is corrupt and void.”

The plaintiffs’ “fraud on a power case” was that Gina Rinehart as trustee of the Trust acted for the purpose of conferring on herself directly or indirectly the ability to acquire the Trust’s shares in Hancock Prospecting Pty Limited in the event that she was removed and replaced as trustee and to deny her children the ability to realise their beneficial interest in the Trust.

However, Brereton J ultimately found that based on the evidence available to the Court the actions taken by Gina Rinehart were not for an ulterior purpose and understandable. In fact Brereton J said:

Properly understood, [the actions taken] were a reasonable response to the benefits accruing indirectly to the Trust… when contextualised to the nature of the business of Hancock Prospecting Pty Limited and the magnitude and extent of risks which its business experiences and was likely to experience, then [the actions taken by Gina Rinehart] can be seen as an appropriate attempt to act fairly towards the beneficiaries.

Change of Trustee

Actually, all of the parties eventually agreed that Gina Rinehart should be replaced as trustee of the trust. However, they could not agree on who would replace her.

At the final hearing, the plaintiffs proposed the appointment of Bianca, with an advisory trustee pursuant to section 14 of the Trustees Act 1962 (WA).

The defendants in the proceedings (including Gina Rinehart) proposed that three trustee companies be appointed jointly as managing trustee. Broadly, this involved utilising the apparatus provided by section 15 of the Trustees Act 1962 (WA) to appoint a licensed professional trustee company as managing trustee to exercise the powers and discretions conferred on the trustee under the Trust.

Considerations in appointing and removing trustees

The dominant consideration in appointing (and removing) a trustee is the welfare of the beneficiaries.

In Mendelssohn v Centrepoint Community Growth Trust [1999] 2 NZLR 88, the New Zealand Court of Appeal said (at 97):

“If there is a general principle, it is that the Court’s task is to appoint the person or persons best suited to administer the trust in the circumstances prevailing.”

Brereton J took into consideration a number of factors including:

1. the possibility that a pre-emptive right of another unrelated party may be triggered resulting in the trust losing its shares in Hancock Prospecting Pty Limited if Gina Rinehart’s proposal was accepted;

2. the wishes of the beneficiaries; and

3. the appropriateness of the individual beneficiaries put forward by the parties.

Ultimately, Brereton J concluded that whilst Bianca Hope Rinehart’s appointment was not ideal – largely because she was also a beneficiary and there was a potential for a conflict of interest to arise and she lacked the experience of a professional trustee – it was far less unsatisfactory than the alternative and said:

“Her appointment also accords with where the predominant weight of the wishes of the beneficiaries lies. For those reasons, Bianca is better-suited than any of [the other professional trustee companies put forward] to administer this Trust in the prevailing circumstances.”

Bianca Rinehart’s appointment was conditional on her undertaking to:

a) provide regular statements of Trust assets and accounts to the beneficiaries;

b) retain suitably qualified lawyers, accountants and or financial advisors to advise and assist her in managing the affairs of the Trust where necessary;

c) not sell, or give a transfer notice in respect of, any of the Trust’s shares in the fourth defendant Hancock Prospecting Pty Limited, without either the consent of all the beneficiaries of the Trust, or the advice of the court;

d) not commence or continue proceedings on behalf of the Trust in a court, tribunal or arbitration without the advice of the court, provided that this does not preclude the commencement of proceedings for urgent interim relief;

e) unless she is of the opinion that in any particular case it would be contrary to the interests of the trust to do so, consult the beneficiaries before seeking the advice of the court and disclose to the court the views of the beneficiaries when seeking such advice.

Foulsham and Geddes notes that this article is written for the purpose of providing generalised information and not to provide specialised legal advice. If you require qualified legal advice on anything mentioned in this article, our experienced team of solicitors at Foulsham and Geddes are here to help. Please get in touch with us on 02 9232 8033 today to make an enquiry.